Big Funds and Small Players: Powering Innovation in Defence

The increasing geopolitical tensions and the heightened commitment to defence spending by nations...

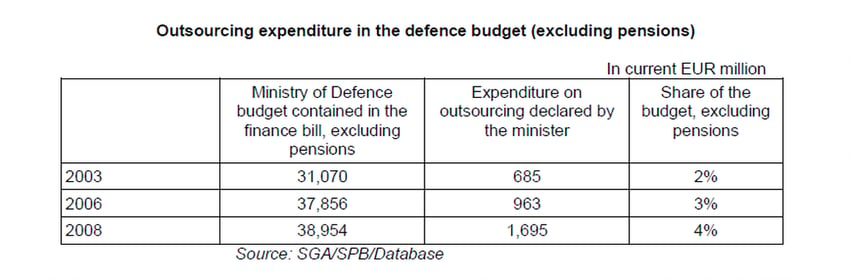

In September 2011, the rapporteur of the MEC (control and assessment mission of the financial committee on outsourcing in the field of defence), Louis Giscard d'Estaing, recalled that 25% of the British budget was outsourced, as opposed to 6% in France.

In 2014, 9% of the budget excluding pensions was outsourced.

At a time when France is struggling to renew its equipment and when major programmes (FREMM, PA2, modernisation of the navy RAFALES to F3 standard, FELIN, NH90, A400M, SCORPION, purchase of GOWIN[1] or OPV, CAESAR MK1 and 2 and TRAJAN, FAMAS FELIN, upgrade AZUR on LECLERC tanks……), crucial to the material renewal of our armed forces, are either delayed in a troubling way as regards the maintaining of our operational capacities or are simply indefinitely postponed, should outsourcing be used further and faster? Can the British 25% be reached and under what conditions? Is this desirable considering the inevitable losses in internal competencies that outsourcing will cause?

If one is to believe the last two administrations (Sarkozy, Hollande) the answer is yes. Arithmetically, and apart from all other considerations, outsourcing will enable to regain the capacity to invest and purchase material essential in maintaining our operational capacities.

What does this reform, which is reflected in the French General Review of Public Policies (RGPP) by the conservative government and recently extended by the current Minister of Defence and in the setting up of a project company (a French adaptation of the PFI in the military sector), provide? This reform relies primarily on a reduction in staff of approximately 54,000 personnel enabling, without a budget increase, to free up 2,7 billion EUR worth of credit. Beyond that, what are the functions that can be outsourced and that affect the budget of the armies in a structural manner?

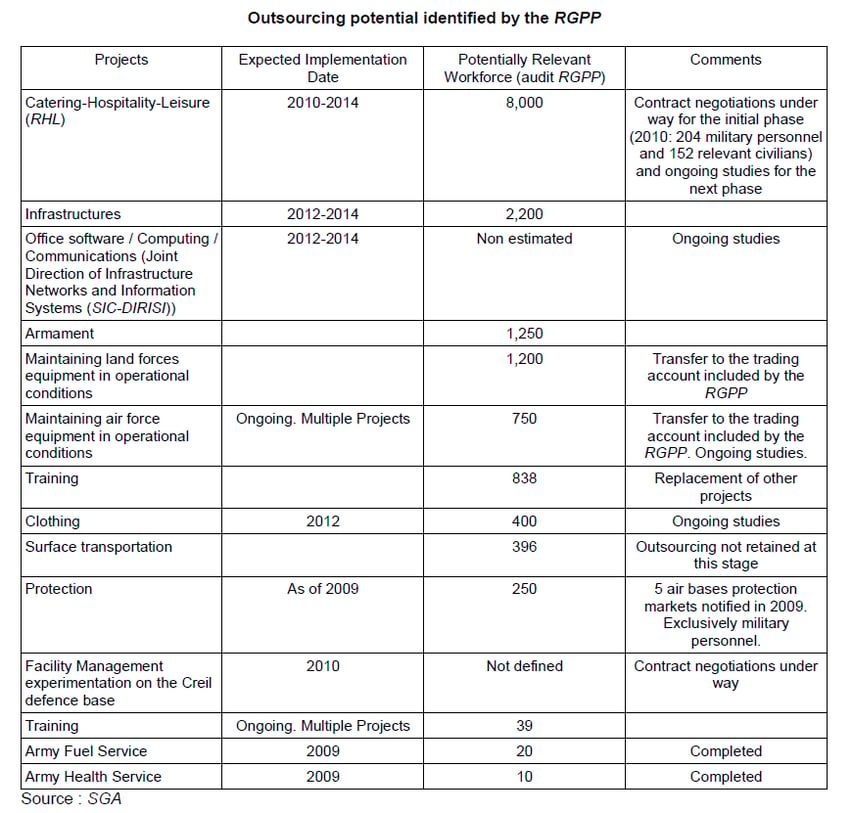

They can be found virtually everywhere as demonstrated in the following examples:

Indeed, if we take the time to carefully read the conclusions by the Court of Auditors, beyond the 54,000 jobs referred to by the RGPP, it is possible to consider that 16,000 extra jobs can be optimised within the armies.

In resuming some of the conclusions provided by the Court of Auditors, it is possible to establish the typology of outsourcing and pinpoint the reasons why the ministry has recourse to such outsourcing. We can identify several types:

In the "Hospitality / Catering" sector, the current plan includes a reduction of 350 people which, according to the Court of Auditors, could be increased to 8,000 people.

Aviation Maintenance in Operational Condition (MCO), outsourcing will allow a reduction in 750 jobs; and could concern, in the end, 1,900 jobs.

The usufruct of military communication satellites (SYRACUSE) will be put at the disposal of private operators against payment (NECTAR operation). In this last case, the significant delay in the implementation of contracts did not allow the initial target - profitability of the equipment to be reached - and resulted in a loss of internal competence with the disappearance in 2012 of the internal competence "Maître de Satellite"[1] by the armed forces.

The last possible type of outsourcing is a PPP (public–private partnership) named "Special Purpose Company[2]" allowing private operators to finance, with State capitalisation, materials or installations that the armies cannot afford to own immediately but that are needed urgently.

Mr Le Drian, Minister of Defence recently specified what can be included in the latter framework: the financing of transport aircraft A400M to replace the old C160s, the financing of Godwin[3] class OPVs or of FLOREAL 2 frigates needed by the French Navy in order to carry out surveillance and sovereignty-related missions in EEZs (as well as counter-piracy missions). This lack in vessels leads the Navy to deploy first-rank vessels in this role.

As we can see, the budget optimisation resulting from outsourcing provides again an investment capacity in "major programmes" and the possibility for the armed forces to equip themselves urgently with materials or equipment that are available "off-the-shelf".

This last point should not be overlooked as it can lead to immediate and significant costs

In 2008 a tragic example demonstrates this clearly: adapting packages to combat conditions in Afghanistan following the Uzbin Valley ambush where their incompatibility with operational imperatives was made obvious. This example of adapting the equipment may seem basic but it cost 20 million EUR[1] over 2008 and 2009. This emergency investment was spent on bulletproof vests and ear and eye protective gear.

In short, the RGPP has had satisfying results if one goes by the laws of arithmetic. But beyond the potential success of this policy, and its continuation under a different name by the socialist government with the implementation of "special purpose companies", the ministry and the armies wish to set its limitations. In this case, the Anglo-Saxon experience and the 10 billion EUR in outsourcing of the British Ministry of Defence also show the limits of this policy not to trespass.

Indeed, this outsourcing, relative to strategic or combat competencies, must not be allowed to slash the internal skills base and to let it fall below the minimum threshold that enables:

It is on this basis that the armies want to ensure that by using outsourcing contracts, they are not forbidden to preserve a minimum basis of technical and patrimonial capacities enabling them to keep all necessary operational independence when confronted with private partners whose commercial aim among others is to make the "client" prisoner of their know-how or capacities.

An example of the latter is the capability reduction in our means of air transport that are currently being outsourced to private companies (Salis Contract and Atares Protocol), and that affects our operational capacities in overseas operations.

In a sensitive operational sector, such as strategic transport, the Ministry of Defence considers that outsourcing aims at satisfying exceptional peaks of activity that do not justify investing heavily beyond the indispensable "base" which guarantees the autonomous functioning of the armies on a day-to-day basis.

However, this is not the case since 92% of strategic transport (in tonnage), in favour of prepositioned troops or troops in overseas operations, is carried out through 49 outsourced markets. In total, a third of strategic transport spending of the French armies is outsourced. This situation reveals an acknowledged capability structural deficiency, the armies having only 41% of the operational contract means which is far from the indispensable base. Even if the ministry does not consider that resorting to outsourcing penalises its functioning, it is to be feared that in a major crisis the availability and, therefore, the cost of the means of strategic transport to charter in a tense global market make their mobilisation unreliable.

Although resorting to outsourced support or transport means represents an economical interest (for example, avoiding unnecessary investments in transport in mainland France), or an operational one (chartering small volumes in emergencies), one should seriously ponder the base of patrimonial capacities necessary for outsourcing to be a choice and not something imposed. And yet, the decisions to finalise different deals were made through a case-by-case approach in order to meet urgent needs and compensate for growing capability shortages. The creation in 2007 of the transport multimodal centre, in charge of coordinating all the means used by the armies, only rationalised the management of deficient means.

Outsourcing strategic transport is therefore imposed and indispensable as it compensates for a capability structural deficiency.

In addition to these outsourcing contracts, since a patrimonial deficiency is observed and the air force's investment capacity has been reduced, the solutions are

In the case of the first solution, let us note that this type of partnership has also its limits. A recent example was given when Germany refused to honour the protocol as the French Air Force was tempting to evacuate some of our nationals in Libya.

The second example that was mentioned in this article above is one of the corollary of the NECTAR operation: the transfer of the SYRACUSE satellites usufruct to a private actor in telecommunications.

Again, the outsourcing of a strategic element leads to a loss in highly strategic human competence because the armies' global communication capacity by way of a space connection is at stake.

Thus, if we follow the hard-earned lessons of the British Ministry of Defence, losing a competency is a very long-term loss. Learning it again and in-sourcing it again are processes more costly than the initial benefits of outsourcing.

The Ministry of Defence is showing its willingness to make it easier for SMBs to have access to defence markets, particularly in outsourcing. The commitment of the Ministry to the SMBs Pact (Pacte PME), the setting up of specific support measures, and the signature in February 2010 of a charter of good practices are just a few examples of this willingness. However, the data available does not give any indication that the conditions under which SMBs have access to defence markets are satisfactory.

Furthermore, the ministry was unable to provide statistical data that would enable to measure their effects. The cases examined by the Court showed that SMBs were guaranteed access only concerning basic service activities (notably cleaning, maintenance, transport), and that these were also subject to concentration in favour of large firms, as is already the case in the catering business.

The Ministry is faced with a contradiction: on the one hand, supporting the SMBs; on the other, supporting the main objective of outsourcing, that is, achieving savings in operating costs. This is illustrated in the difficulties encountered in drawing up support functions management contracts ("Facility Management"). Regulations concerning the allotment of public procurements, as provided under article 10 of the French Public Procurement Code which protects SMBs, seem to require a strict interpretation, as shown in the judgement of the Administrative Court of Lyons (a company of the group Pizzorno Environnement, 7 April 2008) concerning the cancellation of the contract regarding the outsourcing of services to the military camp Canjuers.

The opportunities are nevertheless the most important with regard to Facility Management activities. According to the firm Valois Conseil, which is based in Paris (partner to Victanis) and led by former Deputy Michel Grall (defence specialist and former rapporteur of the Defence Committee of the French National Assembly), it is estimated that the market is bolstered by the following elements:

The budget allocated to the support of the defence bases amounts to 749 M EUR (Finance bill 2015).

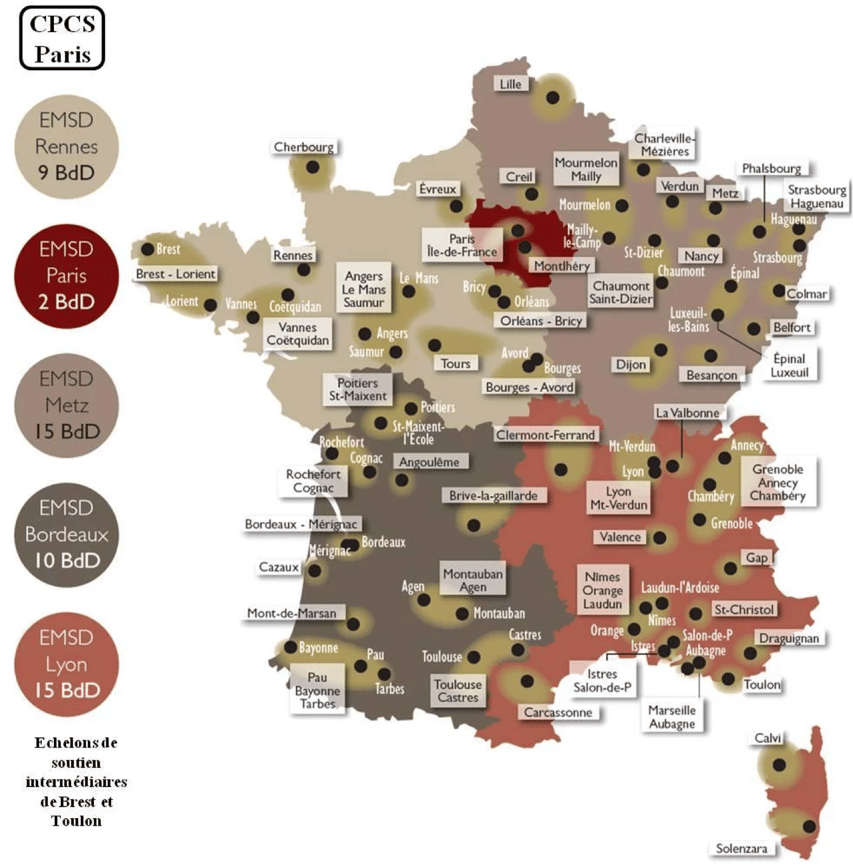

The 51 defence bases (see Map on Defence Bases) have started to reform their purchases taking into account the practices of the other ministries and resorting to shared purchasing services.

They modify their policy on current expenditure contractualisation by notifying markets over longer periods and by preparing themselves to globalisation.

Map of the Defence Bases (Source: SGA 2011))

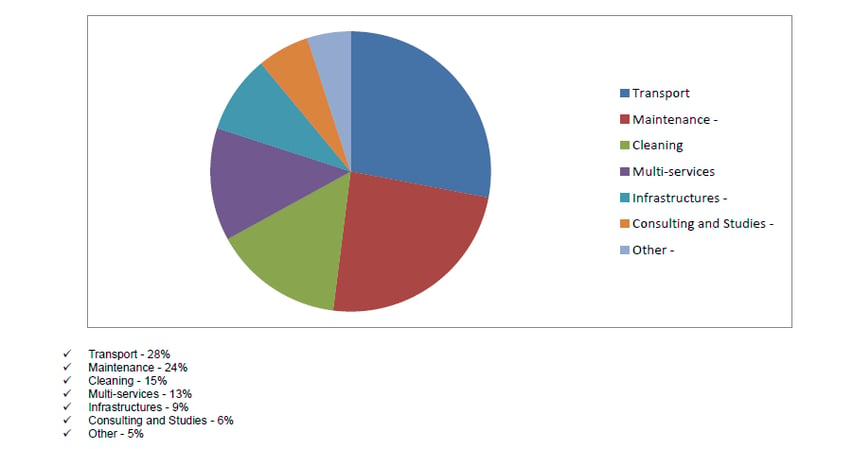

In terms of support, the bulk of the outsourced operations is based on several distinct sectors:

Catering – Hospitality – Leisure (RHL)

Infrastructures (renovations, operating, maintenance)

Office Software and Communication Sciences

Clothing

Multi-services

Transport and logistics (including and excluding Maintenance in Operational Condition)

This outsourcing policy was at first a means to meet the needs related to the elimination of conscription and the move towards professional armed forces.

After being conducted on a case-by-case basis, the policy on outsourcing is henceforth an inherent part of the Ministry of Defence reform. It is used in order to allow the ministry to make true savings, to help refocus on operational activities, to obtain improvements on costs and service quality.

The Ministry of Defence formalised four criteria of expediency to clarify his decisions:

not affect the capacity of the armies to fulfil their operational missions

ensure in the long run significant economical and budgetary gains

preserve the interests of personnel through redeployment conditions

not favour the creation of oligopolies among suppliers and allow SMBs to have access to these markets.

Finally, the decision is now made by comparing an economical solution based on having recourse to external providers with a solution based on preserving an extensively reviewed on-site activity.

The end of conscription, budget cuts and the need for the armies to refocus their investments on combat tools are as many elements that lead the French actors (the State, the Armies, the DGA (the French Defence Procurement Agency) and the SGA (the French General Secretariat for Administration)) to no longer have a sole ideological approach but have from now on a pragmatic, economical and operational approach driven according to specific parameters in coordination with the General Staff.

If France wants to be equipped with the necessary means to tackle capability shortages which weaken its operational capabilities, it must absolutely generate savings in operating costs enabling it to re-equip its armies with modern materials in sufficient quantity and with a steady budget.

The conduct of such a policy over the long run, which is to be continued beyond one to two government terms regardless of their political colours, no longer follows political criteria but is simply guided by objectives that are dictated by the daily operations of the armies, and the military objectives assigned to our armed forces and economic constraints.

Sources :